"The built work of the Italian architect Alberto Ponis is concentrated in the extraordinary rocky coastal landscape of northern Sardinia, where he has lived since 1964. This series of houses, many of them holiday homes, together have today been recognised as a major body of work, their designs combining a thorough knowledge and training in International Modernism, honed by Ponis having worked with Ernö Goldfinger and Denys Lasdun in London, with a response to and deep understanding of the local landscape or cultural condition – key examples of what Kenneth Frampton termed “critical regionalism”.

Born in Genoa in 1933, Ponis studied at the University of Florence, before going to London in 1960 to work at the offices of Goldfinger and then Lasdun. He returned to Italy in 1964, to set up his practice in Palau, Sardinia. One of his key early houses there is Casa Hartley, built overlooking the sea in 1970, whose strict geometries of plan nevertheless merge into its bizarre rocky surroundings. The architect Sebastiano Brandolini, a friend of Ponis and editor of a new book, The Inhabited Pathway, describes the very special journey and sense of passage that a visit to this house involves.

The landscape of the Costa Paradiso in the district of Trinita d’Agultu e Vignola is truly epic. Its bizarre, sharply pointed rock pinnacles, set close together, look as if they have once been the nests of prehistoric animals or the unidentifiable fossilised remains of some creature that once lived here. It is a landscape akin to America’s Far West and could even be likened to Monument Valley on the border between Arizona and Utah, even if no desert plateau lies at the feet of its rocky outcroppings.

All the movement in the landscape of the Costa Paradiso, from the continuous ups and downs between the valleys to the dales, ridges, pinnacles and cliffs, tends to make visual orientation rather difficult, in part because the roads follow a logic that is quite different from the topography. It is possible for two houses to be just a few hundred metres apart but hidden from each other’s view, while the road that links them may be several kilometres long. Then, from around a corner, the sea emerges on the opposite side from the one where you left it just a few minutes ago, and even when the sea can be reached from these houses, you still need to tread warily over those sharp-edged rocks. And because the waves are often whipped up by the powerful mistral wind, you have to really want to go for a swim. There are few beaches and even fewer moorings. Many houses are equipped with mini swimming pools set back, high up on the hillside, like watchtowers drawing their water from the sea below.

Casa Hartley actually occupies a dip in the ground between two of the pinnacles. The staircase of the house is deceptive, because in photographs it looks as if it were built on a large scale, but in reality, it is small. It is as if you had ended up on an Alpine pass with the land rising and falling away in all directions: it rises steeply towards the two juxtaposed pinnacles, rolls gently away towards the interior, and falls away sharply towards the sea. Ponis made a scientific study of the morphology of the land on which the house was to settle down as if on a bedsheet. The site is practically a miniature version of the wider landscape, and to study and conceptualise it required a host of different tools: walking over the ground in boots, carrying sketchbooks, making drawings, using photography – not to mention being able to view the site from close up and from a distance. The indigenous plants (whose trunks in Sardinia sometimes seem as old as the rocks themselves) formed part of his study, and by integrating them into the design as it was coming into being, Ponis anticipated and headed off the threat that in the future the owners might decide they wanted a little garden, flowerbeds, planters, a grassy lawn, irrigation systems, and non-native plants such as cactuses, oleanders, and bougainvillea.

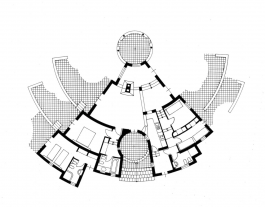

The footprint of Casa Hartley is triangular in shape and covers about 120 square metres. It has a sail-shaped roof (whose pantile covering distinguishes it from the masonry roofs of the houses dating from a few years earlier) that physically extends the form of one of the two neighbouring rocky pinnacles; it is actually this similarity that makes the structure fit into this place so perfectly.

The inside rooms defined by sections of the circumference, each with its own centre, enjoy access to all the paved terraces outside, which are set at the same level as the ground and are designed using the same geometry. Compared to the spacious and elegant (and also better built) houses which Ponis designed for a more demanding clientele from the 1990s onwards, this building seems to combine a Franciscan frugality with a warm congeniality. In its plan, two circles mark out two points that on the outside anchor the house to the place and on the inside fix the two extreme ends of the living room. The first point signals the end of the pathway that you walk along from the car and which bids you welcome by making you feel that you are being admitted into the house, while the second point, set on one corner of the triangle, is just an impression on the ground that assists you when leaving the house. From here, in fact, you can climb up a daring staircase – some of its steps made from stone blocks, some carved directly out of the rock – until you reach the rock pinnacle to the left, which is the lower of the two. There is a miniature belvedere here, which allows you to isolate yourselves even further from the world; by climbing just a few metres you have passed from being “down in the valley” to being “on top of the world”. The relationship that Ponis asks you to have with the environment is not Platonic or picturesque, but carnal and direct. For anyone who comes here on holiday, the epic panoramas of the Costa Paradiso may also lose their spectacular Far West-like appearance and become more domesticated presences, perhaps even useful in some ways."

Sebastiano Brandolini is an architect who teaches at ETH Zurich and practices in Milan, in partnership with Alba Gallizia. He was editor of Casabella from 1984 to 1996 and is presently working on a book on urban walking in Milan. The introductory text and following text by Brandolini above is cited from The Inhabited Path: The built work of Alberto Ponis in Sardinia. Park Books, 2014.

Name: Alberto Ponis

Location: Sardinia, Italy

Type: Places

Posted: November 2020

Categories: vernacular architecture, sustainable design, raw materials

"The built work of the Italian architect Alberto Ponis is concentrated in the extraordinary rocky coastal landscape of northern Sardinia, where he has lived since 1964. This series of houses, many of them holiday homes, together have today been recognised as a major body of work, their designs combining a thorough knowledge and training in International Modernism, honed by Ponis having worked with Ernö Goldfinger and Denys Lasdun in London, with a response to and deep understanding of the local landscape or cultural condition – key examples of what Kenneth Frampton termed “critical regionalism”.

Born in Genoa in 1933, Ponis studied at the University of Florence, before going to London in 1960 to work at the offices of Goldfinger and then Lasdun. He returned to Italy in 1964, to set up his practice in Palau, Sardinia. One of his key early houses there is Casa Hartley, built overlooking the sea in 1970, whose strict geometries of plan nevertheless merge into its bizarre rocky surroundings. The architect Sebastiano Brandolini, a friend of Ponis and editor of a new book, The Inhabited Pathway, describes the very special journey and sense of passage that a visit to this house involves.

The landscape of the Costa Paradiso in the district of Trinita d’Agultu e Vignola is truly epic. Its bizarre, sharply pointed rock pinnacles, set close together, look as if they have once been the nests of prehistoric animals or the unidentifiable fossilised remains of some creature that once lived here. It is a landscape akin to America’s Far West and could even be likened to Monument Valley on the border between Arizona and Utah, even if no desert plateau lies at the feet of its rocky outcroppings.

All the movement in the landscape of the Costa Paradiso, from the continuous ups and downs between the valleys to the dales, ridges, pinnacles and cliffs, tends to make visual orientation rather difficult, in part because the roads follow a logic that is quite different from the topography. It is possible for two houses to be just a few hundred metres apart but hidden from each other’s view, while the road that links them may be several kilometres long. Then, from around a corner, the sea emerges on the opposite side from the one where you left it just a few minutes ago, and even when the sea can be reached from these houses, you still need to tread warily over those sharp-edged rocks. And because the waves are often whipped up by the powerful mistral wind, you have to really want to go for a swim. There are few beaches and even fewer moorings. Many houses are equipped with mini swimming pools set back, high up on the hillside, like watchtowers drawing their water from the sea below.

Name: Alberto Ponis

Location: Sardinia, Italy

Type: Places

Posted: November 2020

Categories: vernacular architecture, sustainable design, raw materials

CONTACT

We're based in Berlin for most of the year. Our mobile office likes to follow our European vision, traveling around to where PIONIRA takes us.

CONTACT

Instagram →

Facebook →

Spotify →

More →

© 2021 PIONIRA

Imprint. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy