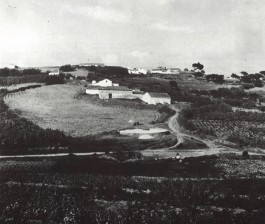

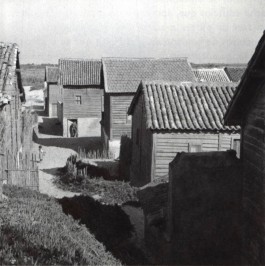

This zone takes in Estremadura and a large part of Ribatejo and Beira Litoral. It is a zone of transition and contrast. The north is damp and green while the south is drier. To the north of the River Tagus the land is given over to mixed farming which encourages scattered towns and villages. In the centre there are hamlets and in the northern part small settlements which in flat areas tend to be strung out along the main roads in an orderly fashion (roadside communities generally reduced to one-street hamlets. On the more rugged coastline, seaside communities are well-structured and compact like the older villages of the interior. Communities on the flat lands of the Ribatejo tend to be concentrated down long, wide, rectilinear streets bordered by one storey houses, wine cellars, presses and occasionally a carriage entrance opening onto its respective courtyard. On the Setubal peninsula the whitewashed towns and villages have a closed look about them and the houses are isolated from the street.

On the less rugged coastline to the north of the zone the communities have wooden houses open to the outdoor life of the fishermen and their families which takes place right in front or their homes. Besides the appearance of the villages and houses of the region there are other typical features of the urban or rural scene. Some of these include fountains; market places or fair grounds; common wells between the Sintra hills and the Torres region, some with extensions for the animals; common wash houses; areas for local dances or the spaces reserved for the game of quoits; the bandstands common on the southern bank of the Tagus opposite Lisbon; large, solemn bull rings; the hostels for pilgrims the finest example of which is the centre planned for pilgrimages to Our Lady of the Cape at Cabo Espichel, the work of peasant pilgrims of the Lisbon region («saloios») in 1757.

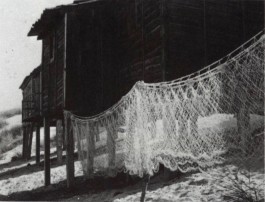

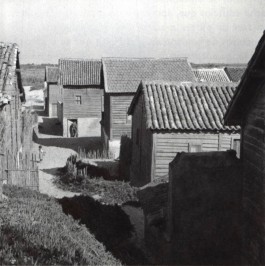

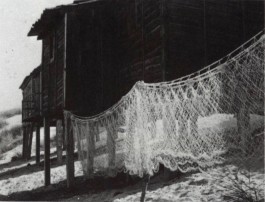

There are other buildings dependent on the economy of the region. The whole windy coastline of Estremadura is scattered with windmills. These are circular in plan and built of stone, and when built of wood, triangular, as found in the pine forest region of Leiria. Tide operated windmills are found on the southern bank of the Tagus between Alcochete and Alfeite, but they are now in ruins due to the competition introduced with mechanical milling. Wine cellars and wine and olive presses are part of the local scenery as well as «salt houses, austere buildings in stone or wood standing between the salt flats (Alcochete). Lime kilns blend into the surrounding countryside; and fishermen's homes made of wood stand near the Leiria pine forest accompanied by the shed for fishing tackle and the boats and stables for the oxen that pull in the nets; rural shops are generally connected to the home of the owner; the houses of itinerant labourers («avieiros»), men and women who come from Vieira-de-Leira to work in the Ribatejo, and who build their houses on piles to protect them from flood waters; the Islanders's Houses (« Casas dos Ilheus»), which are an unusual example of collective rural habitation for agricultural workers at Picanceira, Matra.

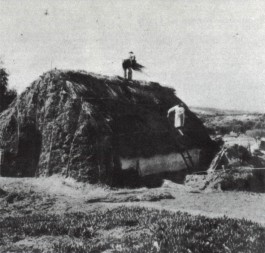

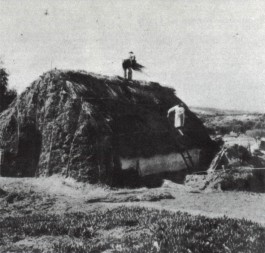

The materials used are naturally those at hand such as stone, (almost always limestone) whitewash, abobe, loam, wood and thatch.In places where limestone and basalt are found the old Roman tradition continues of paving floors in ornamental patterns contrasting the black and white stone. Brick is used to fine effect throughout the Ribatejo and Estremadura and is seen on screen walls, round gardens and as facing on buildings. The marked regionalism in the use of adobe and loam determines the type of house with low, sturdy walls, almost without windows, and supported by buttresses. However, these archaic materials are rapidly being substituted by cement blocks. Whitewash is used invariably throughout the Ribatejo and Estremadura as in all areas under Mediterranean influence. It covers the whole house, and even the roof in some seaside communities (Peniche). In the area where timber predominated in local architecture concrete has been sensibly substituted, thanks to the idea of structure known to those skilled in the use of wood. Props, pillars or cross-beams, retaining the proportions of the wood formerly used, are built naturally and correctly.

Although Estremadura and Ribatejo are among the most prosperous regions of the country, there are essential privations due to the low standard of living (lack of the most basic hygienic facilities, furniture, primitive habitation al plans, flooring of beaten earth). Despite all this the people have managed to create a certain harmony between local construction and the environment with a formal sincerity and natural feeling for space. In other words they have managed to overcome their innumerable material needs and reach a high level of artistic awareness. For various reasons they have managed to create a variety of architectural styles.

The low-lying coast of the pine forest of Leiria. Here buildings are of wood and built on pillars to be free of the sand. The plan is rectangular with one, or sometimes two, floors , in the case of the latter the ground floor is used for storage . The tiled roof is two sided .The kitchen is connected to the varandah , and the living - room gives directly onto the exterior.

Interior fringe of the pine forest of Leiria. In this part buildings are low and made of adobe or loam. The doorway is wide and shaded by a porch at the front of which are one or two half walls on one or both sides of the entrance to the porch. This arrangement creates a pleasant combination of light and shade. Successive rooms are built on, such as the oven, outhouse, stable or storage shed and all this gives an interesting appearance to the straggling layout which includes the two gabbled roof where inset glass tiles illuminate interior rooms. Above all this rises the chimney.

A «saloio» region between the Sintra hills and the Mafra area. Buildings are of stone, cubic in design and topped off by a four, or sometimes, two, gabled roof. Whether in the villages or in the fields they are surrounded by dry stone walls. Indoors life goes on around the entrance hall cum living-room on either one or two floors. In the primitive ground floor home the kitchen and bedroom always have direct connection with the entrance living-room Where there are two floors a stairway leads from the living-room to the bedroom or bedrooms on the upper floor.

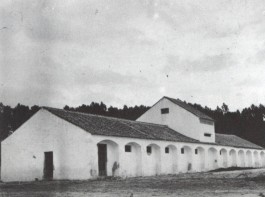

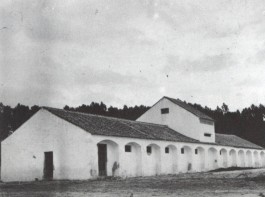

Ribatejo. Buildings are of brick, soft lime stone or adobe, with one floor only. Intercommunicating rooms join one another in succession resulting in an elongated rectangular plan. Additional units are the shed, oven and cellar. The well proportioned chimney rises above the two gabled roof . Everything is whitewashed but the lower part of the house walls, the corners and the door and windows frames, and sometimes even the walls themselves, are painted in black, ochre, blue, vermilion or green. Interior flooring is of beaten earth watered with a dilute solution of clay which gives it a reddish or yellowish colour.

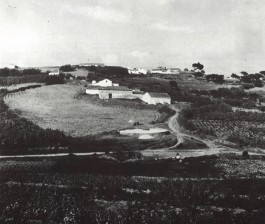

Setubal peninsula. Here the one storey houses are long as one would expect in scattered communities. The walls are of adobe or loam, have very few openings, are low-ceilinged and the whole has a very closed appearance. The home itself is divided up by light wooden partitions. Successive annexes are added and the oven, plus the wide chimney, and sometimes buttresses all go to make up a neat, solid, whitewashed set of buildings contrasting attractively with the green of the countryside. Buildings of a religious, municipal or courtly nature are, as in other zones, more or less influenced by formal architecture. Rural churches with a forecourt and porch, and the square complete with bandstand. Chapels with a large porched in area preceding the entrance. Seaside chapels with a dome or pyramid shaped roof. Town Halls in the town square where the pillory stands. In country mansions, as in other buildings showing evidence of semi-formal architectural structure. The influence of the environment and the skill of local labourers added to local construction materials have all left their mark.

This text was transcribed from the English translation of Arquitectura popular em Portugal, Vol. I. published in 1988. All images were scanned from the same volume.

Title: Arquitectura popular em Portugal

Author: Alfredo da Mata Antune/Associação dos Arquitectos Portugueses

Published: Banco de Fomento Nacional, 1988, Lisbon

Type: Book

Posted: May 2020

Categories: architecture, crafts, earth, lisbon, localism, portugal, raw materials, vernacular architecture

This zone takes in Estremadura and a large part of Ribatejo and Beira Litoral. It is a zone of transition and contrast. The north is damp and green while the south is drier. To the north of the River Tagus the land is given over to mixed farming which encourages scattered towns and villages. In the centre there are hamlets and in the northern part small settlements which in flat areas tend to be strung out along the main roads in an orderly fashion (roadside communities generally reduced to one-street hamlets. On the more rugged coastline, seaside communities are well-structured and compact like the older villages of the interior. Communities on the flat lands of the Ribatejo tend to be concentrated down long, wide, rectilinear streets bordered by one storey houses, wine cellars, presses and occasionally a carriage entrance opening onto its respective courtyard. On the Setubal peninsula the whitewashed towns and villages have a closed look about them and the houses are isolated from the street.

On the less rugged coastline to the north of the zone the communities have wooden houses open to the outdoor life of the fishermen and their families which takes place right in front or their homes. Besides the appearance of the villages and houses of the region there are other typical features of the urban or rural scene. Some of these include fountains; market places or fair grounds; common wells between the Sintra hills and the Torres region, some with extensions for the animals; common wash houses; areas for local dances or the spaces reserved for the game of quoits; the bandstands common on the southern bank of the Tagus opposite Lisbon; large, solemn bull rings; the hostels for pilgrims the finest example of which is the centre planned for pilgrimages to Our Lady of the Cape at Cabo Espichel, the work of peasant pilgrims of the Lisbon region («saloios») in 1757.

There are other buildings dependent on the economy of the region. The whole windy coastline of Estremadura is scattered with windmills. These are circular in plan and built of stone, and when built of wood, triangular, as found in the pine forest region of Leiria. Tide operated windmills are found on the southern bank of the Tagus between Alcochete and Alfeite, but they are now in ruins due to the competition introduced with mechanical milling. Wine cellars and wine and olive presses are part of the local scenery as well as «salt houses, austere buildings in stone or wood standing between the salt flats (Alcochete). Lime kilns blend into the surrounding countryside; and fishermen's homes made of wood stand near the Leiria pine forest accompanied by the shed for fishing tackle and the boats and stables for the oxen that pull in the nets; rural shops are generally connected to the home of the owner; the houses of itinerant labourers («avieiros»), men and women who come from Vieira-de-Leira to work in the Ribatejo, and who build their houses on piles to protect them from flood waters; the Islanders's Houses (« Casas dos Ilheus»), which are an unusual example of collective rural habitation for agricultural workers at Picanceira, Matra.

The materials used are naturally those at hand such as stone, (almost always limestone) whitewash, abobe, loam, wood and thatch.In places where limestone and basalt are found the old Roman tradition continues of paving floors in ornamental patterns contrasting the black and white stone. Brick is used to fine effect throughout the Ribatejo and Estremadura and is seen on screen walls, round gardens and as facing on buildings. The marked regionalism in the use of adobe and loam determines the type of house with low, sturdy walls, almost without windows, and supported by buttresses. However, these archaic materials are rapidly being substituted by cement blocks. Whitewash is used invariably throughout the Ribatejo and Estremadura as in all areas under Mediterranean influence. It covers the whole house, and even the roof in some seaside communities (Peniche). In the area where timber predominated in local architecture concrete has been sensibly substituted, thanks to the idea of structure known to those skilled in the use of wood. Props, pillars or cross-beams, retaining the proportions of the wood formerly used, are built naturally and correctly.

Although Estremadura and Ribatejo are among the most prosperous regions of the country, there are essential privations due to the low standard of living (lack of the most basic hygienic facilities, furniture, primitive habitation al plans, flooring of beaten earth). Despite all this the people have managed to create a certain harmony between local construction and the environment with a formal sincerity and natural feeling for space. In other words they have managed to overcome their innumerable material needs and reach a high level of artistic awareness. For various reasons they have managed to create a variety of architectural styles.

The low-lying coast of the pine forest of Leiria. Here buildings are of wood and built on pillars to be free of the sand. The plan is rectangular with one, or sometimes two, floors , in the case of the latter the ground floor is used for storage . The tiled roof is two sided .The kitchen is connected to the varandah , and the living - room gives directly onto the exterior.

Interior fringe of the pine forest of Leiria. In this part buildings are low and made of adobe or loam. The doorway is wide and shaded by a porch at the front of which are one or two half walls on one or both sides of the entrance to the porch. This arrangement creates a pleasant combination of light and shade. Successive rooms are built on, such as the oven, outhouse, stable or storage shed and all this gives an interesting appearance to the straggling layout which includes the two gabbled roof where inset glass tiles illuminate interior rooms. Above all this rises the chimney.

A «saloio» region between the Sintra hills and the Mafra area. Buildings are of stone, cubic in design and topped off by a four, or sometimes, two, gabled roof. Whether in the villages or in the fields they are surrounded by dry stone walls. Indoors life goes on around the entrance hall cum living-room on either one or two floors. In the primitive ground floor home the kitchen and bedroom always have direct connection with the entrance living-room Where there are two floors a stairway leads from the living-room to the bedroom or bedrooms on the upper floor.

Ribatejo. Buildings are of brick, soft lime stone or adobe, with one floor only. Intercommunicating rooms join one another in succession resulting in an elongated rectangular plan. Additional units are the shed, oven and cellar. The well proportioned chimney rises above the two gabled roof . Everything is whitewashed but the lower part of the house walls, the corners and the door and windows frames, and sometimes even the walls themselves, are painted in black, ochre, blue, vermilion or green. Interior flooring is of beaten earth watered with a dilute solution of clay which gives it a reddish or yellowish colour.

Setubal peninsula. Here the one storey houses are long as one would expect in scattered communities. The walls are of adobe or loam, have very few openings, are low-ceilinged and the whole has a very closed appearance. The home itself is divided up by light wooden partitions. Successive annexes are added and the oven, plus the wide chimney, and sometimes buttresses all go to make up a neat, solid, whitewashed set of buildings contrasting attractively with the green of the countryside. Buildings of a religious, municipal or courtly nature are, as in other zones, more or less influenced by formal architecture. Rural churches with a forecourt and porch, and the square complete with bandstand. Chapels with a large porched in area preceding the entrance. Seaside chapels with a dome or pyramid shaped roof. Town Halls in the town square where the pillory stands. In country mansions, as in other buildings showing evidence of semi-formal architectural structure. The influence of the environment and the skill of local labourers added to local construction materials have all left their mark.

This text was transcribed from the English translation of Arquitectura popular em Portugal, Vol. I. published in 1988. All images were scanned from the same volume.

Title: Arquitectura popular em Portugal

Author: Alfredo da Mata Antune/Associação dos Arquitectos Portugueses

Published: Banco de Fomento Nacional, 1988, Lisbon

Type: Book

Posted: May 2020

Categories: architecture, crafts, earth, lisbon, localism, portugal, raw materials, vernacular architecture

CONTACT

We're based in Berlin for most of the year. Our mobile office likes to follow our European vision, traveling around to where PIONIRA takes us.

CONTACT

Instagram →

Facebook →

Spotify →

More →

© 2021 PIONIRA

Imprint. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy